Among School Children by William Butler Yeats: Summary

The poem Among School Children was composed after the poet’s visit to a convent school in Waterford Ireland in 1926. This poem moves from a direct consideration of the children to Yeats’ early love, Maude Gonne, and then to a passionate philosophical conclusion in which all of Yeats’s platonic thinking blends into an exalted hymn of raise to the glory and the puzzle of human existence.

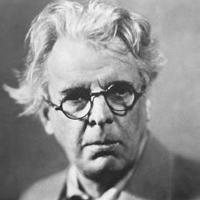

William B. Yeats (1865-1939)

As Yeats entered the school, he was received by an old nun who conducted him through different classes. The children in the classes looked with wonder at the sixty year old smiling public man (poet). At the sight of children, he is reminded of Maude Gonne; his beloved as she must have been a student like the girls who stood before him at the time. He recalls a particular day when she had told him how trivial incidents and reproof from the teacher would make her unhappy and turn the entire day into the cheerless void.

The poet had listened to her account and expressed sympathy, till he completely identified with her: it was as if there two selves seemed to blend into one like the yolk and white of an egg. At this point, there is an allusion of the myth that claims that man and woman were originally one, but since they forcefully separated, they always attempt to come together.

The poet’s thought keeps visualizing the image of Maude Gonne and he looks upon this girl and imagines that Maude Gonne, too as a child very much like the girl now standing before him. No doubt her beauty was classical like that of Helen, the daughter of the Leda. The color of the cheeks and the hair of one particular girl reminded him of the complexion of his beloved; his imagination runs wild and he sees her as if she were actually standing before him.

The poet then recalls the feature of Maude Gonne in her old age. Her cheeks were hollow; she was old and decrepit and looked as if she subsisted on the wind and shadows in place of water and solid food. Even so, she was still a good model of a work of art. Naturally poet is reminded of his own old age. He was quite good looking once. Though not as beautiful as Leda, but it is useless to brood over youth and beauty that was now a thing of the past. One must always remain cheerful and keep smiling, showing to the world that even if one has grown a scarecrow, one is a comfortable kind of scarecrow. Old age and death are awful realities. One should accept the inevitable and make the best of a bad situation.

In the sixth stanza the poet ridicules great philosophers of the world in a light hearted vein. Plato, the famous philosopher regarded the world as unreal, a mere reflection of ideas. On the other hand, Aristotle was a practical minded man of action and, as the tutor of Alexander, must have chastised that great conqueror frequently. Yet another philosopher Pythagoras declared that he was ‘golden thighed’. He was a great musician himself and could listen to the music of the spheres or the musical sounds emanating from the movement of planets in their orbit. But all the outstanding knowledge and wisdom of these renowned men could not prevent the natural process of ageing. Their philosophies notwithstanding, they grew old and broken like a scarecrow with the passage of time.

Passionate lovers, loving mother and pious nuns all stick to illusions. Their fondness for cherished images makes them blind to hard and harsh reality. The beloveds are not at all as good and beautiful as they are imagined, sons never as handsome and dutiful as believed or supposed, and the God is in heaven never as just and merciful as generally understood. And yet this worship of images continues unchanged. The fact is that the images stand for glorious ideals which are hardly ever attained. These idols mock at all human efforts. They are mockeries of the heart as great philosophers are mockeries of the intellect. None of them can change the facts of life or influence the course of nature.

The last stanza is an emphatic re-affirmation of the poet’s maxim that life is an organic whole made up of opposites. Just as chestnut tree is neither leaf blossom or trunk, but the sum total of all three, so also man is neither mind nor body nor soul but an untitled entity of the three. Life becomes really fruitful and labor is truly rewarding when the diligence of the scholar does not make him clear eye. Just as a dancer cannot be isolated from the dance, so also the body cannot be separated from the soul. Harmony between the two is indispensable for self-fulfillment for the bloom, and beauty of the tree of life.

Cite this Page!

Sharma, K.N. "Among School Children by William Butler Yeats: Summary." BachelorandMaster, 23 Nov. 2013, bachelorandmaster.com/britishandamericanpoetry/among-school-children.html.

Literary Spotlight

Among School Children: Introduction

Among School Children: Analysis

The Scholars: Critical Analysis

Sailing to Byzantium: Analysis

The Theme of Immortality in Byzantium Poems

A Prayer for My Daughter: Analysis

Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop

The Lamentation of the Old Pensioner

He Wishes for the Clothes of Heaven

An Irish Airman Foresees his Death

When You Are Old: Summary and Analysis

William Butler Yeats as a Symbolist

Truth of Human Life in Yeats's Poetry

Yeats and the Romantic Tradition

The Salient Features of Yeats's Poetry

Biography of William Butler Yeats

|

bachelorandmaster.com |