The Missing by Thom Gunn: Summary and Critical Analysis

The poem 'The Missing' has been taken from Gunn's award-winning 'The Man with Night Sweats'. This poem, like all the others, responds to the real AIDS crisis in the 1960s and 70s in America. Gunn, a gay poet living in San Francisco, responds to the crisis in an unsentimental, unwavering verse.

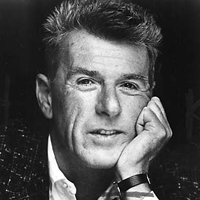

Thom Gunn (1929-2004)

By exposing the agony and affliction brought on by AIDS, Gunn chooses an aesthetic strategy that might elicit empathy from readers who have never had a direct experience with the disease. Night sweats can be an indication of an AIDS infection even before a blood test identifies the disease. The resulting sinister sense of terror is seen throughout the poem and is ultimately encapsulated in the futility of the speaker’s final gesture. Gunn had seen the impact of AIDS firsthand while he was living in San Francisco.

His mother is singing and he is pressing her feet. But she does not feel disturbed by her son’s behavior. She smiles at him and goes on playing. The poet knows that it is his romantic past. He wants to live in the present facing the reality. But the woman is very clever at singing. Her song is so sweet and her playing is so skillful. The poet wants to control himself, but he cannot. This time he goes back to his boyhood. He supposes that he is in his warm and comfortable room. It is very cold outside. It is Sunday evening (holy day). All his family members are there. They are singing hymns. The piano is guiding them.

The main theme of the poem is based on a number of contrasts. There is also the contrast between the traditional structure and the postmodern subject of homosexuality. It is written in a rigorous, traditional form with rhymed couplets. The controlled form and restrained emotion contrast with the horror and powerlessness that the poet feels in the face of the ravaging disease. The poem contrasts the narrator’s memories of the time before AIDS with the effect that the disease has on his community. In the second and third stanzas, Gunn describes a time before the plague in an almost utopian imagery. He seems to have found a romantic freedom after the gay rights movements of the late 1960s, when gay men and women could more openly explore their sexuality. He points out, “contact of friend let to another friend/supple entwinement through the living mass/ which for all I knew might have no end, / Image of an unlimited embrace.” He envisions a community so close that it becomes one “living mass” possibly embracing all humanity.

A few stanzas of the poem do arouse a positive kind of feeling, especially when he remembers the pleasant past when his friends were past; but even then the language is punctuated by puns, ambiguities and dark ironies. The second and third stanzas promote an ideal of freedom, for the remembered times before AIDS were characterized by “ceaseless movement” in which the poet was “Aggressive as in some ideal of sport”. Gunn combines his interest in freedom with humanism. The humanism of the poem deepens the tragedy, for the narrator’s loss is not just personal; it includes the loss of a community. The death of any member of the community diminishes the narrator, leaving him unsupported and alone. The narrator is part of a large human mass dying piece by piece. The poem undercuts the pleasant memories of the second and third stanzas with bitter irony. The contact of friend with friend, which so appeals to the narrator, spreads the disease, making it more insidious. The utopian unlimited embrace degenerates into a potential apocalypse.

Another striking stylistic feature of the poem is the use of its imagery, basically that of the statue used to compare with the speaker’s own body. The narrator compares himself with a statue several times and in a different sense. To create a sense of immobility, Gunn compares himself to a statue so immobile that its calves and feet are unfinished. The pain of immobility gains further, significance if one considers that praise of action. Without the community’s “supple entwinement”, he feels unfinished. The statue imagery furthermore brings into the poem the contrast between introspection and violent action, an important theme in Gunn’s career. Incapable of action or even movement, the statue only ruminates over its anxieties. The poem closes on a bleak note, “I find no escape”. There is no way for the narrator to return to the last world of ceaseless movement and the unlimited embraces. Gunn’s AIDS poem ends with “no consolidation, transformation, or epiphany”. In addition, the poem displays another hallmark of Gunn’s poetry: a complex and seamlessly rendered formal structure. Written in iambic pentameter and also a traditional rhyme scheme (abab), “The Missing” is a unique example of a traditional formal poem taking a contemporary them as its subject. It is an image of both friendship and desire, two sources of empowerment and identity. But, it is also an image with the dark shadow of death looming over it, suggesting the infection and the tragedy to which desire can lead. The images of the statue, the eyes glaring and the body mutilated, creates a sense of terror that those who find homosexuality repugnant also empathize with a man who has been “bared” by the death of his community.

Gunn expresses freely what complex state of mind a fatally diseased man undergoes exploring the intimate emotions. Modern day American and other countries have a number of gay communities which are until now called perverted people indulging into the unnatural sex appetite. But the poet releases from himself the hesitation and seeks freely to mean how remorseful the life becomes once we contract the diseases like AIDS.

Cite this Page!

Sharma, Kedar N. "The Missing by Thom Gunn: Summary and Critical Analysis" BachelorandMaster, 19 Nov. 2013, bachelorandmaster.com/britishandamericanpoetry/the-missing.html.