Lullaby by W.H. Auden: Summary and Critical Appreciation

Lay Your Sleeping Head, My Love, entitled Lullaby, is one of the finest love-lyrics of W.H. Auden. It was first published in New Writing, Spring 1937, and later included in the Collected Shorter Poems, 1950. The theme of the poem is love caught at its most intense movement. The poet tells of night of love, but the beauty of that night is impaired by his consciousness that it has been snatched from the chaos. The experience is related to its social setting. The charm of physical love is limited only up to the satisfaction of carnal desires till midnight. Freud’s influence is pervasive, but most evident in the second and fourth stanzas.

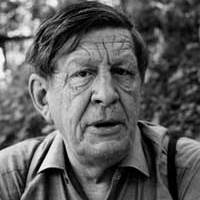

W.H. Auden (1907-1973)

The speaker tells his love to lay her sleeping head on the speaker’s “faithless” arm. He then goes on meditating about how time and sickness can take away a child’s individual beauty. But it does not matter so much as the grave claims us all anyway. However, until the arrival of death, the speaker hopes his beloved would lie in his arms, both alive and “entirely beautiful.”In a pensive mood, he starts to think randomly about varieties things, like Venus (the Roman goddess of love), a hermit who has an ecstatic experience, and madmen who regret the future. But despite all these wandering thoughts, he longs to remember everything that has happened on this beautiful night with his lover. The speaker knows everything finally perishes, the beauty, the romantic midnight, and vision too. Then the speaker looks down at his beloved and prays that his beloved will experience life to the fullest. At the end of the poem, he states that the man is "watched by every human love." It's not God who looks after his sleeping beloved; it's the speaker himself.

In this beautiful love lyric the lover meditates on his beloved’s sleeping head lying on his human though faithless arm. The emotional situation born of the close intimacy between the lovers adds sufficient imaginative force and emotional appeal necessary in a lyric of personal love. Yet, what is remarkable is the content of thoughtful awareness which lies in the loving acceptance of love in spite of its limitations. We notice that in this fine lyric, the sensual ecstasy of a night of love is set against the consciousness of disorder described in the second stanza, the final appeal being intellectual as much as it is emotional. Whereas the sensuous resources of the language evoke an atmosphere of joy, the consciousness of the significance of such a moment arouses an awareness which prevents the poem from being purely an experience of emotional intensity. The lover cannot reject altogether his role of a conscious thinker. Auden is interested more in the idea of acceptance of love in spite of its limitations than in the passionate treatment of the emotional situation. Auden achieves the beauty of its effect by the way in which the moment of happiness is weighed gravely and consciously against an awareness of all that can threaten it. The poem’s philosophical thinking takes us to the fact that since love makes life blessed, and since free choice alone makes love possible and men imperfect, free choice and imperfection are blessed as well. We may call it empirical philosophy. The imperfection is a blessing become the subject of this poem. Though ever imperfect “Life remains a blessing”, and the Speaker asks for his beloved the greatest gift men can receive “the mortal world itself.

Loyalty, evanescence and other allied associations of love are alluded to in the next stanza. And in the last one, love becomes profoundly human free from sheer sensuality. The fading away of time, beauty and vision is brought out in brief references. The ‘pedantic boring cry’ of the ‘fashionable madmen’ evaluating love in ‘Every farthing’ is also there. But transcending all the sleeping beauty lay like the innocent Cinderella, who found “The mortal world enough". Her ‘dreaming head’ could overcome the "Nights of insult,’ ‘By the involuntary powers’ of love.

The lyric is in the form of a dramatic monologue in which the lover addresses himself to his beloved who is lost in ‘swoon’ after the consummation of their love. The poet begins the poem at a delicate point when the lovers had just had the fullest realization of the bliss of their physical union. The lover accepts the limitations of the human character and flesh. And having accepted it, he proceeds to describe his amorous experience with an attitude of tolerance. He acknowledges the fact of human infidelity. Instead of glorifying the beloved as a goddess, as in conventional love poetry, the lover admits that she is a human being with all human imperfections. The lover also is a human-being not free from human imperfections. ‘Faithless arm’ points to the condition of human faithlessness, but this does not affect his love; neither does it detract from the seriousness of the molestation of his love. On the contrary, it intensities the seriousness of his love.

With age and disease, human beings lose their vitality, grow old and die. Even children grow thoughtful, and lose their charm. 'The poet emphasizes the transitoriness of human life and physical love. The human is ephemeral, and so is their love. Human life is short, and it ends with the grave.

The ecstatic experience of the physical union of the lovers leads to spiritual communion. “Despite the ephemeral nature of their love, the lovers experience mystical ecstasy in their physical union with each other. For the moment, their souls break the bounds of the body, and become one, fuse and mingle with each other. Their carnal love is thus transformed into a spiritual union, a source of mystical bliss, such as the hermit experiences in moments of mystic union with God. There is thus no essential difference between the ecstasy of the lovers and the hermit in deep meditation in rocks and glaciers. The physical is thus transformed into the spiritual and, in the words of John Donne, lovers become ‘saints of love’. Carnal love, therefore, is not to be condemned. In its own way, it is as much a union of souls, as much the result of supernatural inspiration, as the experience of the mystic and a source of as great a bliss”. The ecstasy experienced by the mystic in moments of his mystic union with God is not different from the ecstasy which the lovers feel in their sexual union. Hence Auden calls it ‘sensual’. Ecstasy means ‘standing out’, and both in moments of physical and spiritual unions, their respective ‘soul and body have no bounds’. It may be an illusion, but it is not a worthless one.

The lover criticizes the condemnation of infidelity by the ‘fashionable madmen’ who raise their voice against the union of lovers. The lovers will pay ‘every fa'rthing of the cost’. When, once their physical union has ended, they will suffer an emotional recoil and deficiency of feelings. All this will happen in future. From this night onward they will be fully satiated in their love. After having satisfied their carnal desires, they will grow entirely indifferent to each other. The fountain of love will dry up in their hearts. There would be no whisper, no thought, no kiss, and no look. Their love for each other will come to an end.

Cite this Page!

Sharma, Kedar N. "Lullaby by W.H. Auden: Summary and Critical Appreciation." BachelorandMaster, 28 June 2017, bachelorandmaster.com/britishandamericanpoetry/lullaby.html.